Winter 2024

Bill reviews a book on beloved Christian author Elisabeth Elliott, Nigel Biggar's book on colonialism, Loren Wilkinson long-awaited magnum opus, and a fascinating look at the year 1776.

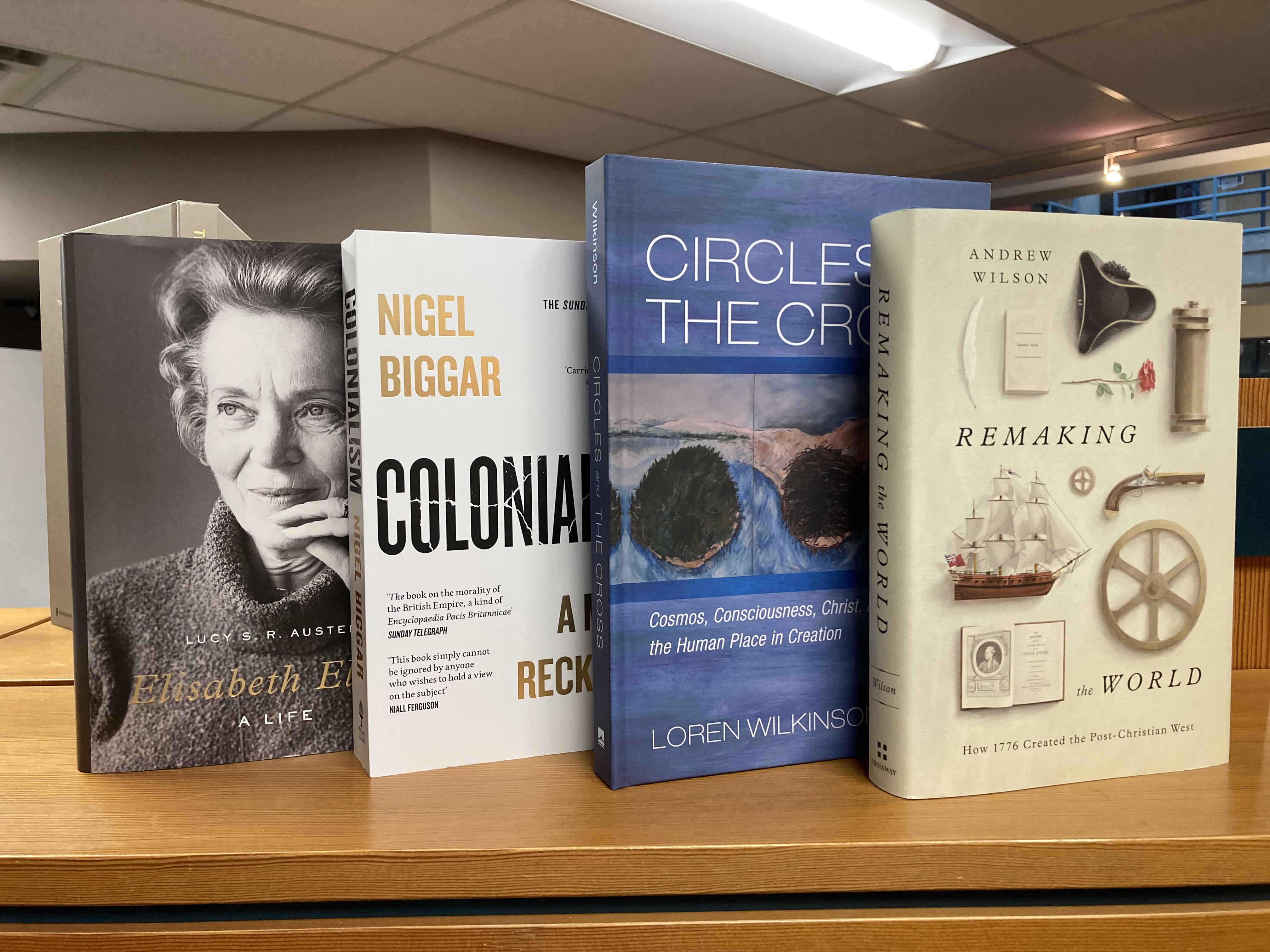

Elisabeth (Howard) Elliot came to public prominence when in 1956 her husband, Jim, was slain along with four other young missionary men in the jungles of Ecuador while trying to reach an isolated tribe known as “Aucas” (Waorani). Photos of the tragedy filled the pages of Life followed by a feature article a year later on the widows who continued to serve on the field in Ecuador. Through Gates of Splendor, written by Elliot and telling the story of the five martyrs, was published by Harper & Brothers in 1957 and became an instant bestseller. A follow-up Life article in 1958 that “shocked the nation” was read by an astounding 76% of American adults, and featured Elliot’s continued missionary work among her husband’s “killers.” Elliot went on to become a well-known Christian writer and came to be viewed as a “formidable” woman and a lightning rod for her outspoken rejection of modern egalitarian gender roles.

The picture that emerges from Austin’s magnificent, 500-plus page biography is that of a “brilliant, difficult and complicated person.” The story takes place across the full background of postwar American evangelical history running through the missionary enterprise, the Bible school movement, fundamentalism, the flavours of holiness teachings, and the prominent evangelical family that the Howard family became.

Wheaton College was formative for Elliot, as well as for her brothers Dave and Tom, and it was here that she became a compulsive journal writer, a voracious reader of books, developed disciplined habits, and where she met Jim. Elliot had a directness to her personality that came across as abrasive but she softened to a degree through new friendships while her faith was shaped through reading and especially the writings of Amy Carmichael. She “shone” in speaking at the Urbana missionary conference in 1972 that was organized by her brother Dave. For decades she was well-known as a Christian public speaker, radio teacher and the writer of 31 books.

Twice-widowed, the topic of suffering was a common theme in her teaching. The “complicated” side of Elliot is the constant theme of the biography but it is her trust in the love of God that in the end stands out to this reader. Austen, a homeschooling mother, with the help of thousands of pages of writing that Elliot left, has surely accomplished something that Elisabeth herself would have admired.

Available for in-store purchase only.

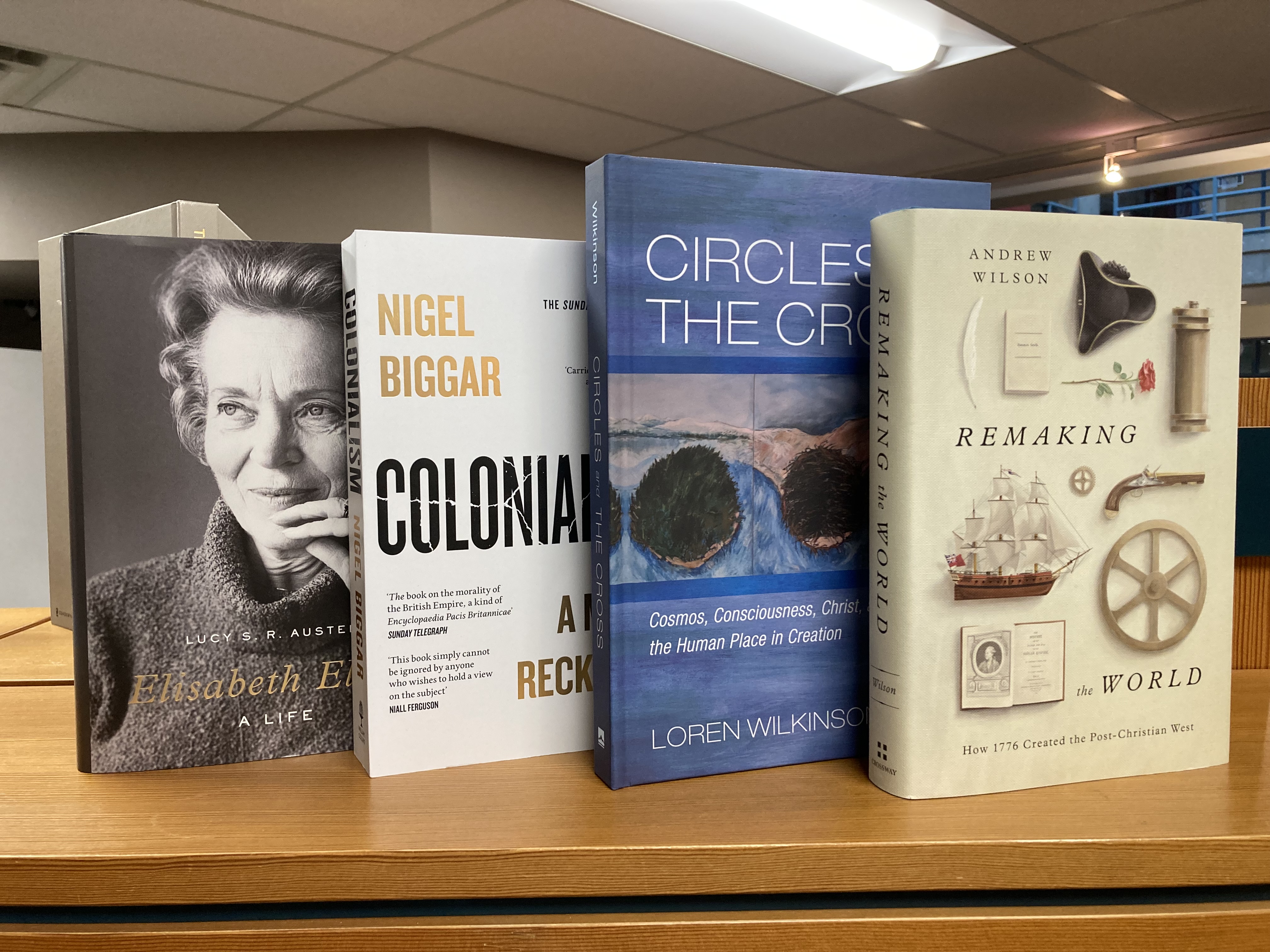

Described as “a moral inquest into the colonial past,” Colonialism was dropped like a hot potato by its original publisher before being picked up by Collins. Scottish-born Oxford theologian Nigel Biggar waded into controversy several years ago with well-placed newspaper op-eds that appeared in the midst of the statue-toppling brouhaha. Central to the book is the topic of the British Empire. Even though Imperial Britain was guilty of a host of injustices, by the 1800s it was committed to the Christian principle that slavery was an evil that warranted abolition, even at great cost (‘econocide’ according to one historian). Abolition constituted a moral revolution, unique in the annals of history.

Biggar’s discussion ranges beyond slavery and includes judicious comments on Canada’s residential schools. (Bigger is not unfamiliar with Canada, being one of Regent College’s most illustrious grads.) His is a defence of the British Empire that I generally find persuasive but it remains an interpretation of a broad canvas portraying tragic, innumerable events and massive movements of peoples over time that cannot be neatly summarized, even in a text with more than 100 pages of footnotes.

The counterpoint to Biggar is Legacy of Violence: A History of Violence by Caroline Elkins (Knopf, 2022). Focussing on the 20th century, Elkins, an historian, argues that Britain’s underlying doctrine was a racism that relied on an “unrelenting violence” to preserve its imperial interests. In order to do this Elkins largely avoids a discussion of abolition in the previous century and the larger and ongoing humanitarian impulses that continued in Britain into the 20th century.

Available for in-store purchase only.

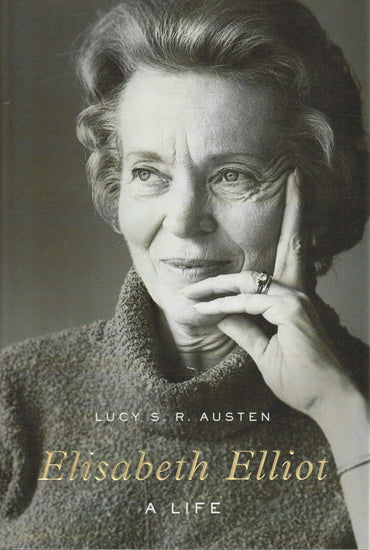

Loren Wilkinson is, among many endeavours, a philosopher, literary scholar and student of science but these cannot be abstracted from the decades of living with his wife, Mary Ruth, on Galiano Island on the Pacific Coast of Canada. While baking bread in an oven, tending a substantial garden and orchard on their farm, being active in the church and community life of the island, and hosting hundreds of former Regent College students who continue to return like migrant birds, Circles and the Cross slowly took form out of this lived experience and reflection as the author looked out on the waters of the Trincomali Channel.

Peter Harris in the Introduction writes that the book “is a Babette’s Feast of a work.” Beginning with a recognition of the wonder of the mystery of human consciousness we are asked to ponder: Why in a vast universe that is beyond human comprehension, should we humans be the only creatures that we know of with the intelligence to be aware of this vastness? Wilkinson then draws us to the wonder and beauty of the cosmos and the continual search to find ourselves within it. At the midpoint of the book, we are introduced to a science that “is the foundational myth of our age” in contrast to a traditional view of science that saw a creator God as the origins of all that exists and the story that holds our culture together. Romanticism and new religious quests emerged from that human longing in the face of the harsh Scientific Enlightenment.

Throughout Circles and the Cross are planted reminders of the wonders of Creation and warnings of its fragility in the face of the activities of us humans. What sets this book apart from, say, the writings of a brilliant thinker such as Iain McGilchrist, is the Cross and Incarnation of Jesus Christ. Particularly in the Gospel of John we are intimately introduced to the significance of the Incarnation within Creation. The Celtic Cross symbolizes the self-giving love of God at the centre who connects and gives meaning to the cycles of earth and cosmos. Following the crucifixion, it is the resurrection of Jesus that enables us to see the power of the God who first formed the cosmos. Concluding an almost meditative discussion of the Incarnation is that old carol by the fourth-century Christian poet, Aurelius Prudential:

Of the Father’s love begotten,

Ere the worlds began to be,

He is Alpha and Omega,

He the source, the ending He

Of the things that are, that have been,

And the future years shall see,

Evermore and evermore.

This reader has only begun to partake in the richness of the feast but I intend to return to this table many times in the years to come.

Available for in-store purchase only.

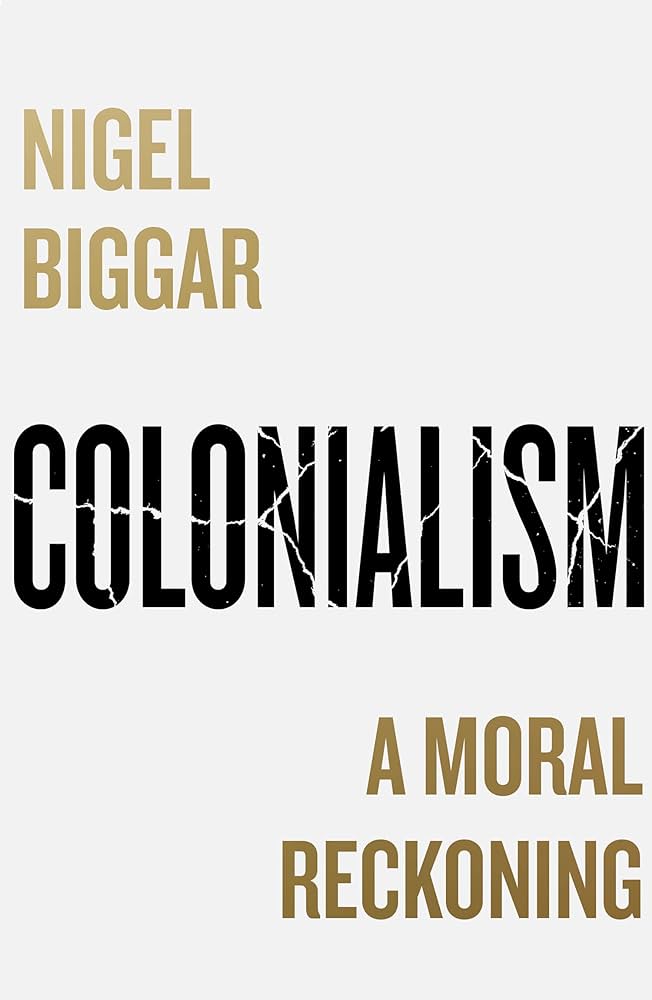

One would not expect a teaching pastor in a large and thriving London congregation to have the time to pen a volume that has been described by historian Thomas Kidd as “an intellectual tour de force and a model of Christian scholarship.” The focus is on a single year, 1776, and seven developments arising from events during this year: Globalization, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, the American Revolution, the beginnings of post-Christianity, and Romanticism. More than any other year 1776 made us Westerners who we are today. Wilson weaves a whirlwind story from fascinating and even “weird” facts. For example, there still lives today a 95-year-old gentleman whose father’s grandfather, tenth U.S. President John Tyler had been a college roommate of Thomas Jefferson! The cultural and technological change across these three generations was staggering.

In the last third and the “heart” of the book are the stories of individual Christians including John Newton, Hannah More, William Wilberforce, Johann Georg Hamann and Rebecca Protten (a former slave turned Moravian missionary). These Christians were part of a vast movement of awakenings and revival in the 1770s and their lives offer a “metacritique of the Enlightenment” while pointing “the way to a post-secular future.” In telling this grand narrative, Wilson’s purpose is to “teach us about living as Christians in our WEIRDER world”: Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic, Ex-Christian and Romantic.

There is no going back to an unretrievable past. But the message of the grace of God turns WEIRDER ways upside down. Remaking ends with the pastoral encouragement to be faithful and obedient and a reminder that genuine revival comes from God’s initiative. This is a book that I will recommend again and again.

Available for in-store purchase only.