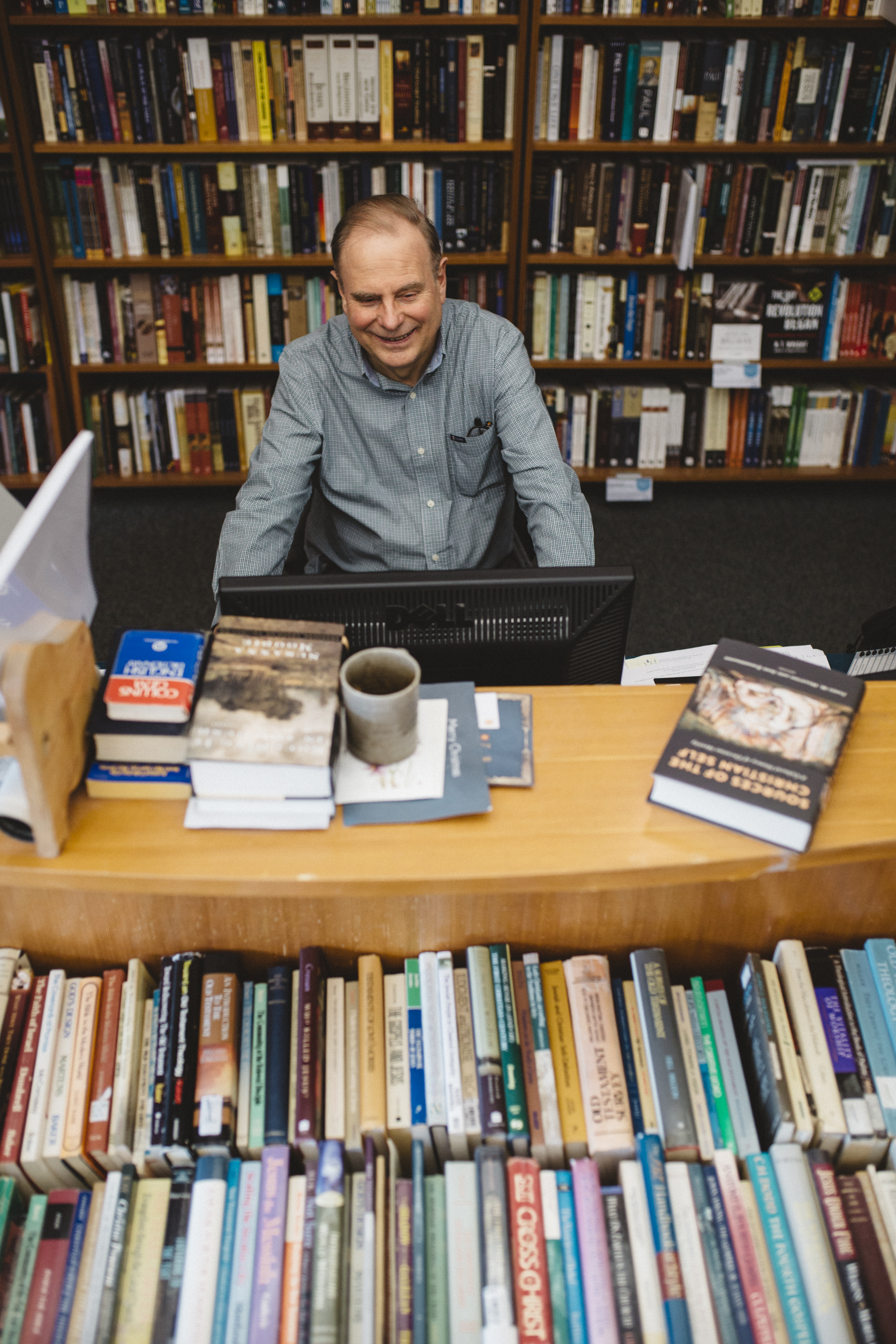

Bill on Books - January 2021

One of the tasks that I enjoy is ordering new titles for the store. In a year I pour through hundreds of publisher catalogues as well as reading thousands of reviews published in New York Review of Books, The Times Literary Supplement, Christianity Today, New York Times Book Review, First Things, Englewood Review of Books, plus the endless book mentions on blogs, in op-ed columns, word-of-mouth, and it goes on. The end result is that here at Regent Bookstore it is Christmas every day and regular shipments of books arrive! All this reading tends to give a bookstore buyer knowledge that is a mile-wide and hopefully a little more than an inch deep. In thinking on this I have decided to start sharing short reviews under the heading of Three Inch Reviews. I have spent years in close proximity to so many titles that I have not actually read even if having an acquaintance with many of them, and even readily recommending them. In this last part of my bookselling career I am thinking it would be good to share some of this knowledge with brief summaries. Here is my latest installment.

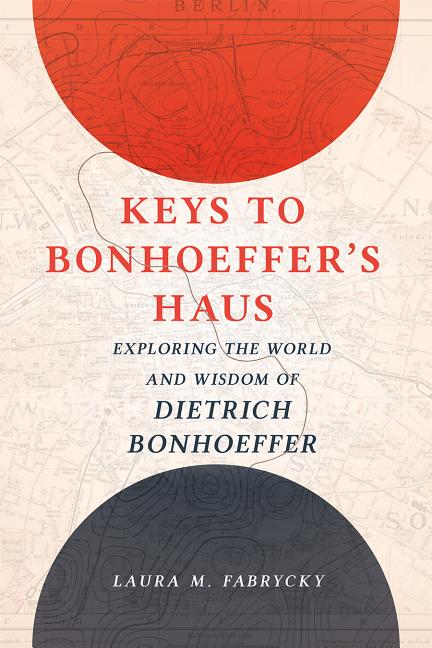

In the summer of 2016, Laura Fabrycky moved with her husband, a U.S. Foreign Service officer, and her young children to Berlin. Finding that they lived a short distance from the Bonhoeffer Haus – Marienburger Allee no. 43 – she made an appointment for her family to have a tour, the week of the US Presidential Election. Rather than a museum, Fabrycky sensed a home. On her fourth visit she joked to the guide that she was visiting so often that she should become a guide herself. The guide responded that, “Yes!” she should. Before long she was handed the key to the house and began her work as a volunteer. The book is a record of her reflections on her own life and story through her encounter with the life of Bonhoeffer. While the reader learns details about Bonhoeffer, the book is a spiritual memoir. Her collected insights she metaphorically calls “keys” – for example: When we hold on to the truth, we find the truth holds on to us, even when we are tempted to despair. She takes us through the house and beyond to important places in Bonheoffer’s life. “Place” is a constant theme as is the importance of “civic housekeeping”–love of neighbour, including those different from us, is expressed in the small details of life. Fabrycky’s training in political theory adds nuance to her cultural insights both past and present. There is much for a Christian to ponder in the pages of this finely written book. An immediate takeaway for me was that I purchased an English copy of the annual daily meditation book, Die Losungen, published by the Moravian community and used faithfully by Bonhoeffer, that pairs an Old Testament and a New Testament verse. Daily meditation on short scriptural passages was a practice of Bonhoeffer and his circle of Confessing Church pastors, and is one for us to continue in these times.

Available for in-store purchase only.

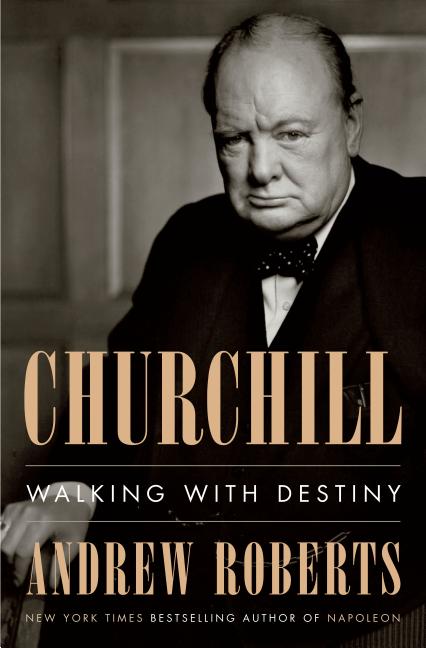

In the long line of Churchill biographies, this is one to be reckoned with. Weighing in at 3.6 pounds, I could only sample sections of the book before returning it to the readers’-in-waiting line at the Vancouver Public Library. The “Destiny” in the title makes one wonder if Andrew Roberts is using it as a proxy for Providence, even if he only admits to using it in a deistic sense of fate. In the introduction, the author quotes a one-time minister in Churchill’s war cabinet as saying after the war that the one instance in which he thought that he could “see the finger of God in contemporary history” was Churchill’s arrival as Prime Minister at a “precise moment in 1940.” Hmm. Roberts is guarded on this and emphasizes that Churchill was skeptical of Christianity although he allows that on at least one occasion, his wife Clementine recalled that when he became Prime Minister, Churchill said “God had created him for that purpose.”

For the Christian reader Churchill can be an enigma. The pacifist would be quick to condemn the area bombing of German cities during World War II while others would never forgive his part in the Gallipoli fiasco. Some Christians will be open to seeing God at work in Churchill’s life in the way that it was preserved, the leadership training that he received in both the triumphs and failures of his younger years, and then in that great moment when he came to power at a time when Hitler needed to be stopped. On this side of the demise of the British Empire, Churchill is out-of-step in his advocacy of it. But one could ask counterfactually whether Hitler could have been stopped apart from that empire? Certainly America would have been a barrier to world domination but the question begs to be asked. Roberts coyly points out the span and complexity of Churchill’s life: “In the year that Churchill was born a British general forced King Koffee of the Ashanti to end human sacrifice; in 1965, the year he died, the Beatles released “Ticket to Ride.” Yes, “Interesting Times” writ large. For a different take on Churchill’s faith by his grandson see: God & Churchill: How the Great Leader’s Sense of Divine Destiny Changed His Troubled World and Offers Hope for Ours by Jonathan Sandys & Wallace Henley, Tyndale, 2015.

Available for in-store purchase only.

The 1960s saw a Baby Boom come of age at a time of cultural crisis. While many shed the Christian beliefs that they had grown up with, those who remained, along with some who were coverts to the faith, often yearned for more authentic expressions of thoughtful and historic Christianity. Two meccas for such young folk were L’Abri in Switzerland, led by an American pastor, Francis Schaeffer, and Regent College in Vancouver, led by the Oxford geographer, James Houston. While differing in important ways, both sought to be places of study within communal settings that placed emphasis upon the “personal” and places where students were free to ask questions, since “all truth was God’s truth.” Both Schaeffer and Houston were deeply pastoral and emphasized the importance of prayer, with Houston placing a special emphasis on friendship with God, knowledge of the self and, out of this, an openness to one another. Neither were places of training for professional clergy, although Regent was a graduate school with a formal course of studies designed for laity. The late 1960s and early 1970s were times of a host of “start-up” activities including efforts to reproduce variations of a L’Abri or a Regent in other settings. “Study centres” is a flexible description that Cotherman uses to describe The Ligonier Valley Study Centre in Pennsylvania, established in 1971, The C.S. Lewis Institute in College Park, Maryland established in 1976, New College established in Berkeley in 1978, and on down to the present which has seen a cluster of study centres being planted on the periphery of major universities in the U.S. Cotherman has told a faith-filled story of a quest to “think Christianly.” May this story help inspire a new generation of young Christians to plant communities of learning and devotion that are adapted to new and challenging times.

Available for in-store purchase only.